This is part one of a two-part discussion with Professor Anthony Johnstone, who teaches Constitutional Law and Legislative & Political Process at University of Montana School of Law. Along with the constitution and legislation, Johnstone writes about and studies election law and campaign finance. Here, he answers questions about voting, the future of the electoral process, and the complex world of campaign finance. Part I focuses on election law, who creates it, and who gets to vote. Part II tackles campaign finance and reform.

What is Montana’s voter turnout compared to other states? Do we have a high voter turnout?

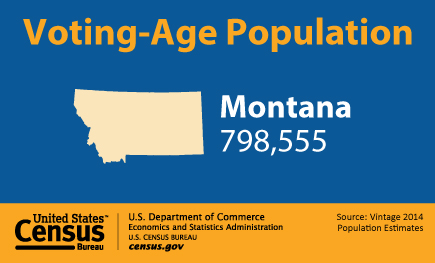

I think Montana has relatively higher turnout rates than other states, just slightly above average. There are a lot of different ways to count turnout. It can be among registered voters, but the better measure is probably voting eligible population. If you want to design policy around getting more voters to turn out, that

Professor Anthony Johnstone teaches Constitutional Law and Legislation at University of Montana School of Law.

policy doesn’t include just getting registered voters to turn out, it should also include the registration process itself, which is the major barrier.

There are two sets of barriers to people voting. One is the registration process and how hard or easy that is and how hard or easy it is to keep your registration current. And the other, and probably largest is then the voting process. We have absentee ballots, and that helps. But we also have elections on a Tuesday in November, and that doesn’t help. So, on balance though, we do slightly better than most states in getting potentially eligible voters both registered and to vote.

What do you see as the biggest problem in our national election system today?

There are two schools of thought on that. The most common complaint you’ll hear from reformers is that it’s not uniform enough. It’s that we should have something like national voter registration. They say we should have a single standard, at least in federal elections, to make sure we’re tracking people to prevent mistakes. We would then resolve the disputes about proper voter identification and voting hours, and absentee ballots. That’s one school of thought and that’s where most reformers are.

The problem with that, is that you make law with the congress you have, not with the congress you want to have. And, of course, congress is a function of the election laws we currently work under.

I guess my view on addressing those barriers is to look at more second-best solutions in the states and to understand that there are places with less-permissive laws with higher voter turnout because of other cultural reasons and we should respect those and understand that. And then the question is, in any particular state, how can that state intervene to nudge voter participation rate up more. And that may be a different answer in every state. It’s not absentee voting everywhere, it’s not same day voter registration everywhere. It’s understanding what makes a particular state’s culture drive its own turnout and how do you tweak that existing culture on the ground on a local basis.

I think there’s a national issue of relatively low voter participation, but there may not be, at least now, a national solution.

What about making Election Day a national holiday? Is that a realistic way to increase voter turnout?

I haven’t seen the evidence on it. It is a state holiday in Montana. State employees get it off, university employees, and students get it off. It’s not clear to what extent it makes a difference. It’s certainly the worst-case scenario to have it on a Tuesday in November. It was originally chosen as market day after the harvest in early American history, not because the people would actually show up.

It’s not clear that making it a national holiday, or even that making it a state holiday, has made much of a difference. Or maybe it has, I just haven’t seen the evidence.

Is there a way that you could foresee that we take politicians out of creating election law? Or, is there an alternative to making it more fair?

Not for federal elections, because that’s in the Constitution. Congress will always have to power to determine the time, place, and manner of federal elections. But it’s possible that if you get congress to stay its hand, then states could develop more innovative solutions, such as non-partisan districting commissions, like we have in Montana. Those could help. Montana has tried to keep politics out of the districting. And there’s no reason to have elected partisan local officials be the point people for elections. It’s possible that you could professionalize and depoliticize that.

But the question is, who would get it? Any state could create a nonpartisan electoral commission like most countries have. But, they don’t, and I think that’s something kind of distinctly and culturally American: We don’t trust bureaucrats with something as important as our politics. The problem is, voters look at that and say “Well, how do you get that job? You probably have to know someone. How do they get there? Will you let the governor do it? Well, the governor will just pick his friends. The senate? Well, that’s just a little better, but they’re still going to pick their friends.” And that’s generally been an obstacle to depoliticizing.

But the question is, who would get it? Any state could create a nonpartisan electoral commission like most countries have. But, they don’t, and I think that’s something kind of distinctly and culturally American: We don’t trust bureaucrats with something as important as our politics. The problem is, voters look at that and say “Well, how do you get that job? You probably have to know someone. How do they get there? Will you let the governor do it? Well, the governor will just pick his friends. The senate? Well, that’s just a little better, but they’re still going to pick their friends.” And that’s generally been an obstacle to depoliticizing.

My view is that you can either wait to have the perfect nonpartisan electoral commission that exists everywhere else but here, or you could use the current electoral incentives that politicians are moved by to get them to do the right thing to increase participation. It seems like the latter is a more realistic strategy than the former.

We think of voting as a general right that we have, but some people are allowed to vote and some people are not allowed to vote. Can you explain who isn’t allowed to vote and what the policy or political reasons are behind that decision?

The U.S. Constitution says very little about who is or isn’t allowed to vote. It just looks to whoever gets to vote for the statehouse in each state. At the federal level, the rule is you can vote for a federal election if you can vote for your state legislature, and the states better not be prohibiting you from voting based on your race, sex, age, or ability to pay a poll tax.

At the state level, states then also have a relatively free hand as long as they don’t discriminate on one of those grounds. Non-citizens can vote in some states. And if a state legislature wanted to allow non-citizens to vote, there’s a little bit of a question, but there’s no obvious barrier.

At the state level, the biggest cohort of voters who are disqualified would be prisoners and/or felons. And while that’s been challenged as a constitutional matter, those challenges have usually failed because the 14th Amendment requires that congressional seats be apportioned by the number of persons there, but also seems to empower states to disenfranchise felons.

However, they are accounted for apportionment purposes. Famously, Montana sees an extreme example of this in the legislative district in Deer Lodge, where the state prison is. A substantial minority of the population is prisoners who can’t vote, but who are counted as being in that district for apportionment.

So, prisoners currently in prison are counted …

Yes. They’re not just counted there to give prison districts more political power, but they’re not counted where they live, which is often urban, and in Montana, reservation-based districts. So, they’re not counted in the residence there. It’s not an enormous effect, but it has a regressive effect on representation in addition to denying prisoners the right to vote.

In Virginia, Governor Terry McAuliffe has taken steps to restore voting rights back to convicted felons. Do you believe this will start a movement, or is he standing alone?

So, here’s an example of external electoral incentives driving a politician, precisely because he’s elected and has friends who he would like to see be elected, expanding participation. Virginia may be a special case because most states are solidly blue or red. Montana is another exception right now. But, most states are either monopoly Democrat or monopoly Republican and you really don’t see innovations one way or another toward more or less participation happening in those states. Or, if they happen they’re less controversial because it’s one party rule in most of the states.

In Montana, our constitution determines that if you’re serving a sentence for a felony in a penal institution or of unsound mind, you’re ineligible, but otherwise you’re eligible. The other states where you would see that have a big effect is Florida and other swing states. I don’t think you’re going to see much movement on that in other states.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

For more on Anthony Johnstone head to his faculty page.

Law Review Articles from Anthony Johnstone:

Recalibrating Campaign Finance Law, 32 Yale L. & Pol’y Rev. 217 (2013)

The Federalist Safeguards of Politics, Harv. J. L. & Pub. Pol. (2016)

A Madisonian Case for Disclosure, 19 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 413 (2012)

By Chelsea Bissell